Pinterest

is a form of digital media (which I will defend throughout the paper,) and is a

new, emerging, and interactive social media outlet. The purpose of Pinterest is

to give its users a format to find and share information. The intended use of

Pinterest is for items, or “pins,” as they are called, to be shared or “repinned.”

In fact, that’s how I came to know about the website. I was sharing interesting

links on my Facebook profile when one of my friends introduced me to Pinterest,

so I wouldn’t need Facebook as a middle-man to relay the information I found on

another site. Pinterest functions by having users import information from an

outside source (a newspaper/cooking recipe website/etc.) and then once it’s on

Pinterest, the link spreads virally throughout the website internally, but I’ll

explain that more in detail later. The main flaw with Pinterest is that while

it is a sharing website, it is currently illegal to share information without

consent from the owner of the link, which then in part makes the whole website

illegal. Pinterest shows how current copyright laws are outdated with new forms

of social interaction.

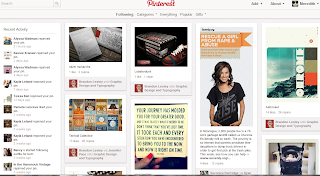

This

is what Pinterest looks like:

Pinterest

is a lot like a virtual magazine and a lot like an online tack board. Imagine

flipping through a magazine, seeing an article that is interesting to you,

cutting it out, and “pinning” it to your tack board to someday return to, to

find again. Pinterest is a website that hosts a variety of interesting objects,

be it pictures, recipes, blog articles, clothes sold on online companies or

anything else imaginable. When the user finds something that they find

interesting, they click on the item and then the “repin” button and that “pins”

that item onto a virtual “board.” A board can be categorized as vaguely or as

descriptive as the pinner chooses, much like a magazine cutter could leave her

articles scattered on her bedroom floor, or could be categorized into a filing

system.

Manovich’s definition of modularity is that it is “The fractal structure of new media…

elements are assembled into larger-scale objects but continue to maintain their

separate identities,” (Manovich 30). That relates to Pinterest because a user

can have a screen of multiple boards, and each board consists of numerous

individual pins- a much like several tiny squares fitting into one bigger box,

and several boxes fitting into a larger box.

Now,

to find items to pin, the user can scroll through a newsfeed of posts that have

recently been “repinned” by people who the user chooses to follow - much like the

newsfeed of information in Facebook. Or, if the user is looking for something

specific, she can click on an organizational button to limit her search. For

example, let’s say a Pinner is looking for wedding inspiration, (which is a

commonly pinned genre.) She would click on the “Weddings and Events” button and

that would bring her to a newsfeed containing every pin within the website that

has been pinned to a board that has been labeled as a wedding board.

Pinterest

can digitally “read” what genre a board falls under (because of the numeric

coding associated with how a Pinner “tags” a post,) and then sorts all boards

of the same kind together. The automation

of this process also defines Pinterest as a digital media artifact because the

numeric coding of tags and the modular sorting of boards lead to a computerized,

completely automatic sorting process (Manovich 32).

So,

the items we pin can be from someone we know personally, if found in our newsfeed,

or we could repin an item that originated from a complete stranger on the other

side of the world. There are numerous ways to find the same link, too. Because

once a link has been repinned, it is now on both the user’s board, and also the

board from which the user found the link. In essence, the link multiplies with

every share. And with every share, the user has the ability to change the

caption of the link. So, the link now exists on the website under a different

tag as well. Consequently, now a link could be found on several hundred

thousand people’s newsfeeds, and potentially under a different tag. Because of

this, there becomes an infinite amount of ways to find a pin. Now, Manovich’s

idea of digital media variability is expressed, because he says, “A new media

object is not something fixed once and for all, but something that can exist in

different, potentially infinite ways” (Manovich 36). A pin multiplies every

time it is repinned, it does not just exist on Pinterest once, but now each

link exists several hundred thousand times, in several hundred thousand

individual locations, in potentially several hundred thousand formats.

Pinning

a pin would be pointless if the links were merely pictures and lead to nowhere.

Pinterest is not an online cloud of saved .jpg’s. The point of Pinterest is to link us to other

sites. A picture of a piece of pie, when clicked, links you to the website that

hosts the recipe for that pie. A picture of a headline of a blog will bring you

to the actual blog where the article was posted, for the user to read. A

picture might link to a tumblr or flickr site. Or a clothing store could post a

picture of a shirt, so when clicked on, the user would be directed back to the

store’s website where they could find the shirt to buy. Anything from anywhere

on the web can be added to Pinterest, categorized for someone to find and be

interested in, and be then linked back to the original host site. It’s almost

like a Google search, except you don’t have to know what you’re looking for.

In

fact, it’s almost like the memex that Bush mentions in his article, “As We MayThink.” It’s a way to store tons of digital information in one place,

categorized and sorted together, to be referenced when needed.

It’s

as though Pinterest is a hyerreality (Baudrillard) of the internet, within the

internet. The whole internet (theoretically) is stored within Pinterest, (or at

least could be,) and the posts that people pin give an indication of how people

want to live their lives. Pinterest has a demographic of upper-middle class

white females between the ages of 15-35. So, according to Pinterest, important

things in life are hair, makeup and clothing styles, foods to try, popular

wedding and home décor trends, and pop culture. Commonly pinned things become

viral, and unpopular topics fade off into the hidden corners of the internet,

to be rarely seen or pinned again.

Now

that we know how Pinterest functions, we can talk about the flaws of its

system. The biggest issue with Pinterest has to do with copyrights.

Having

the interconnectivity with every person who shares the same interest as us, and

every website on the internet, is both a blessing and a curse. While the point

of Pinterest is to share information,

and people post things onto Pinterest so it can be shared, copyright laws say that Pinterest users technically aren’t

allowed to share anything that they don’t have specifically granted permission

for. … So, unless you are able to track the link’s origin (which you may or may

not be able to do because of the tagging system,) and unless you are granted

specific permission from the creator, pinning a post on Pinterest is illegal.

Sometime

last year, a stipulation in Pinterest’s legal section said, ““You

acknowledge and agree that you are solely responsible for all Member Content

that you make available through the Site, Application and Services. Accordingly,

you represent and warrant that: (i) you either are the sole and

exclusive owner of all Member Content that you make available through the Site,

Application and Services or you have all rights, licenses, consents and

releases that are necessary to grant to Cold Brew Labs the rights in such

Member Content, as contemplated under these Terms; and (ii) neither the Member

Content nor your posting, uploading, publication, submission or transmittal of

the Member Content or Cold Brew Labs’ use of the Member Content (or any portion

thereof) on, through or by means of the Site, Application and the Services will

infringe, misappropriate or violate a third party’s patent, copyright,

trademark, trade secret, moral rights or other proprietary or intellectual

property rights, or rights of publicity or privacy, or result in the violation

of any applicable law or regulation.”

A Pinterest-loving lawyer was one of the first people to find this

clause within the website and after that, the questionable legality of

Pinterest went viral.

The point of Pinterest is to find and share

information, and for that information to then be found again. Information is meant

to go viral. Companies and blog writers want their work to be shared as

a way of free promotion. But giving each person (potentially millions) granted

permission to share the site

According

to The Daily Dot, Pinterest workers have since told the Wall Street Journal

that this is just merely a case of the law being behind technology, since all

major websites need to have a section on copyrights, just to cover their asses

in the case that someone tries to pull someone else’s website off as their own.

Sharing, spreading, and repining a link to the website, with credit to the

rightful owner, is in fact perfectly fine, even if the owner doesn’t express

permission for the link to be shared.

There

are millions of sharing sites on the internet besides Pinterest. Sites like

9GAG or The Berry or StumbleUpon are sharing sites. Anything with a URL can be

linked and shared onto virtually any website. The new wave of social

interaction is no longer “Hey, come to my house and look at this link I found!”

but rather now, “Hey, look at this link I sent you!”

It

all boils down to a question: should media on the internet allowed to be shared and linked? After all, it wouldn’t be

published on the internet if the maker didn’t want people to find it, right? And

how could a company ever turn down free promotion to its website? Most

importantly, if a person isn’t illegally, calling someone else’s work his own,

what is the issue with giving the website’s link to someone else?

The

ideas of copyrights, sharing and ownership within digital media are all very

interesting (albeit confusing,) and Pinterest is a fine example of this.

Pinterest, a new and digital media, speaks of the new and ever-changing world

we live in. And I bet, copyright laws soon will be changing to match the viral,

share-able virtual world we live in.

Works Cited

Bush,

Vannevar. "As We May Think." Atlantic Magazine . 07

1945: Web. 26 Sep. 2012.

<http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/>.

Baudrillard,

Jean. “Simularca and Simulations.” Selected

Writings. Stanford University Press, (1998): 166-184.

Kowalski,

Kristen. "Why I Tearfully Deleted My Pinterest Inspiration

Boards." DDK Portaits. ddkportaits.com, 24 02 2012. Web. Web.

25 Sep. 2012.

<http://ddkportraits.com/2012/02/why-i-tearfully-deleted-my-pinterest-inspiration-boards/>.

Manovich,

Lev. "What is New Media?." Language of New Media. (2002):

19-63.

Orsini,

Lauren Rae. "Pinterest Addresses Copyright Concerns." Daily

Dot. (2012): n. page. Web. 25 Sep. 2012. <http://www.dailydot.com/business/pinterest-copyright-infringementlegality-statement/>.

"Pinterest/Copyright

and Trademark." Pinterest. Pinterest, 06 04 12. Web. 25 Sep

2012. <http://pinterest.com/about/copyright/>.